Women's Trauma in Horror

Dissecting the issues of womanhood through fear and morbid storytelling

There are plenty of essays about womanhood and pop culture. This is another one of those essays, so add this one to the growing pile.

In 2023, Barbie took the world by storm with its magnificent and imaginative pink landscapes. While the film fed us visually with its beautiful fashion and home design, it also explored topics of self image, patriarchy/matriarchy, and the overall concept of humanity. “What is womanhood? What is manhood?” are questions the fim posed to the audience through its comedy and its touching moments.

On the other end of the hot pink spectrum are the films oozing of blood.

It sometimes seems as if the discussion of film when speaking about womanhood often overlooks the horror genre. To some degree, it’s understandable as to why: classic films usually made women into damsels, slashers often made them into visual objects, and… I don’t think I have to explain the issues the 2000s presented, considering it was a decade that very heavily criticised women.

In contrast, we have the trope of the “final girl.” A trope that is still used today (and perhaps even played out at this point), making the only character to survive the film be a strong and independent woman. In some instances, she is the one who defeats the villain. In others, she’s simply the only one able to escape the situation.

Final girls aren’t exactly the epitome of horror feminism, however. While characters like Laurie Strode and Sidney Prescott certainly give audiences strong leads, Halloween and Scream surely aren’t films based in exploring the complexities of womanhood, manhood, or anything of the sorts.

We do, though, have films that present the very concept of the woman experience, detailing the traumas people may face. There are two movies specifically, at least when criticizing the issues that society presents upon those who identify as women: Jennifer’s Body and Teeth.

Jennifer’s Body follows Needy Lesnicki and Jennifer Check, high school best friends who have a complicated relationship to say the least.

The main plot point is about Jennifer Check’s transformation of becoming a succubus. Unfortunately, Jennifer was victim to a local band’s attempt at a satanic ritual, wanting to sacrifice a virgin for fame and fortune. Jennifer wasn’t a virgin though, so while the ritual worked for the band, Jennifer was transformed into a succubus.

The beginning of the film explores what Jennifer’s character is: the typical popular girl in high school. She’s pretty, charming, and a cheerleader. Anita (Needy) poses as her opposite, though the two of them are best friends as they had been since childhood.

There’s quite obviously tension between the two. Envy, for one, but also admiration. And, as we later find out, something much more intimate, as they share a kiss on screen.

Jennifer, though she poses as the antagonist of the film, is also the main victim. Her body was sacrificed by money/fame-hungry men so they could get ahead. She was just a stepping stone, nothing more.

Eerily, this imitates the problems that many women have been forced to face in their own lives. More specifically, as was stated in the Vox article by Constance Grady, the film highlighted the disgusting issues that were seen in the media industry. Watching the movie in a post #MeToo world makes the film especially more unsettling. As stated by Grady:

“It’s the story of a group of powerful men sacrificing a girl’s body on the altar of their own professional advancement — and it’s also the story of them using her torment as a bonding activity.”

Jennifer’s Body, then, isn’t some sex fantasy movie as it was once marketed as those many years ago. Rather, it’s a movie about taking revenge on those who took advantage of you. Jennifer uses her body to control her victims, embracing her sexuality as a means of satisfying her hunger.

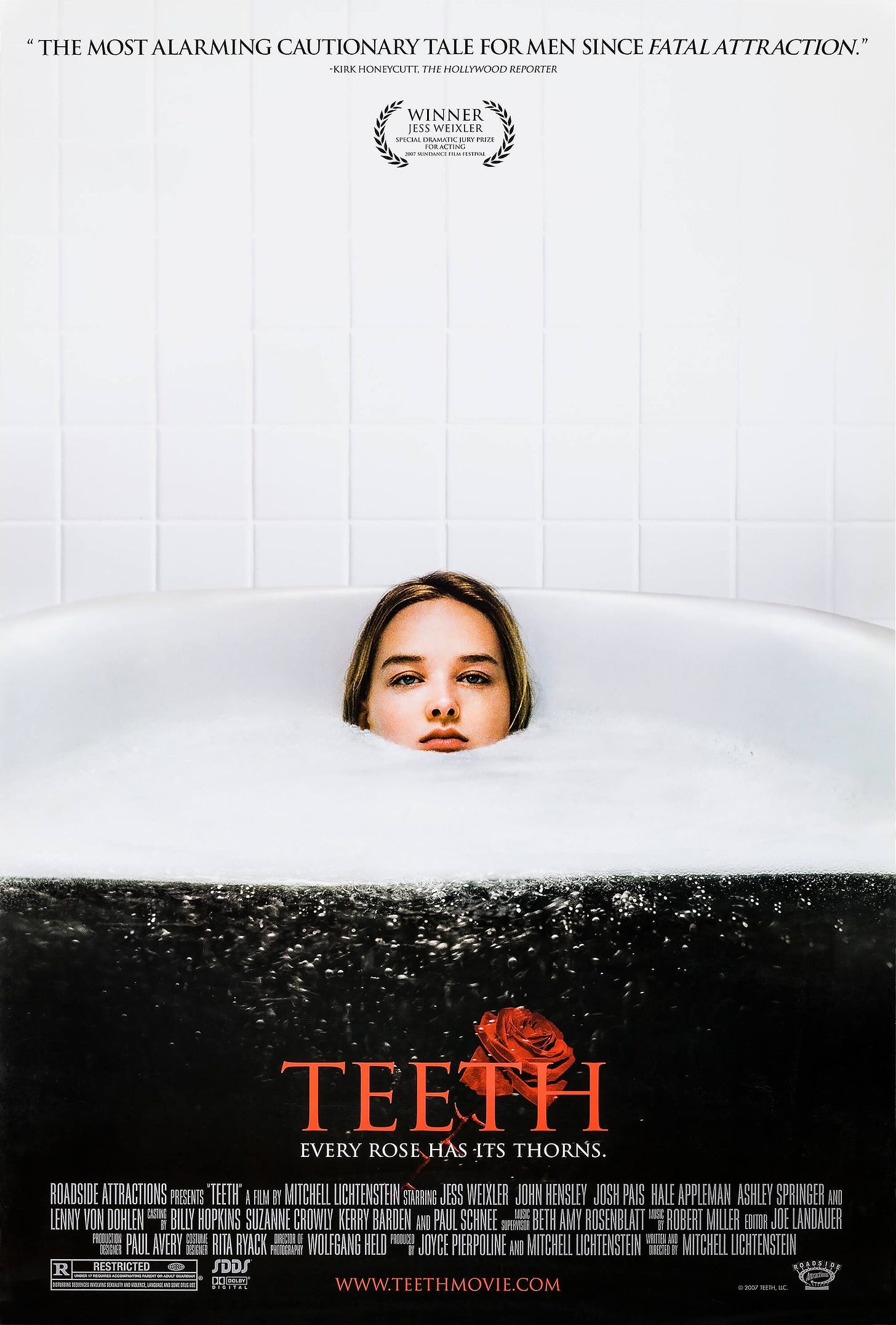

In a similar fashion, Teeth also explores the unsettling reality that many women deal with in terms of their sexual security. Dawn O’Keefe, the protagonist of the film, lives with vagina dentata.

The audience learns of this condition after Dawn escapes a rape attempt, in which her vagina bit off her aggressor’s penis. In fear of what happened, she visits the gynecologist to get checked out, but is then assaulted during the examination by her doctor, resulting in his fingers being bit off as well.

As the movie progresses, Dawn is met with more unfortunate advances. Brad, her step-brother, admits that her vagina bit his finger when they were children, a revelation that prompts Dawn to seek revenge for the loss of innocence that was forced upon her. She seduces him, and like the first victim, bites his penis off.

The last scene of the film shows Dawn hitchhiking, getting into a car with an old man who locks her inside. The film ends with her smiling at the camera.

Teeth is very obviously a film about sexual trauma, more specifically the trauma that many women have experienced in their lifetimes. The most unsettling part of Teeth is that every aggressor was a person that Dawn was supposed to have trust in: her friend, her doctor, and her step-brother. Unfortunately, this is an extremely common reality, and the reason why it feels like such a raw, emotional horror movie.

Sexuality, no matter who it is, is a delicate and sacred thing. The exploitation and thievery of such is nothing short of evil, with many cases never facing proper justice. It’s a situation that both women, men, and anybody who has ever faced sexual assault has to worry about. Even when justice is served, the trauma people are left with outweighs the “win” of the criminal being served prison time.

Teeth simply gives the aggressors a taste of their own medicine. Just as the aggressors violated Dawn, Dawn violates them back, though through means of self-defense. It’s very much an eye-for-eye story in some way, but it’s also a film that highlights sexual violence against women, something that most films try to shy away from.

Slashers films are one of the biggest defenders of using trauma as a means of storytelling. As stated earlier, the final girl trope is a popular device used in the genre, relying on her trauma in order to push her into fighting back against the villain.

Think of the biggest slasher films: Halloween, A Nightmare on Elm Street, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, etc. All of these films end with a final girl, with the character experiencing an immense amount of harassment. They’re stalked, chased, and met with violence at every turn.

In many ways, it mirrors what women have experienced for decades. The same reason many feel uneasy walking home at night, check behind their backs in parking lots, and tightly grip their house keys.

In the end, the final girls are left with a trauma they can never get rid of. Laurie Strode, no matter which timeline you follow, is haunted by her memories of Michael.

Sally Hardesty ends The Texas Chainsaw Massacre with a shot of her screaming in the back of a pickup truck, covered in blood as she watches Leatherface do his iconic dance. A metaphor that even if he is behind her, he’ll always be there with her.

Nancy Thompson, arguably, got the worst treatment, dying to Freddy (though she was able to be the hero in her sacrifice) due to his imitation of her late father. One thing about Freddy, he knows how to use your trauma and fear against you.

Surely, there’s plenty of horror films that showcase womanhood without the trauma that comes with it. One could argue that even something as simple a woman villain is case for such, with characters like Tiffany of the Chucky series being one of them. Tiffany is a strong (though evil) lead, with the only “trauma” she really had being in a shitty relationship and regretting murder for a week.

But that’s an essay for another day. Because female villains are cool. Duh.

Horror is possibly one of the best genres for telling a story about trauma. To be able to translate such experiences into an unsettling yet captivating story helps highlights the issues we see in the world, and letting these stories be told is one of the first steps in the right direction.

Women being able to tell their stories, rather that be through horror or not, is critical for a better understanding of the world. Just as it’s important for men to tell their stories of trauma and to be taken seriously, so is it for women (and our non-binary folks) to do the same.

Love this and can’t wait for the piece about female villains ❤️#tiffanyislife