Suburbia is built upon perfection.

In 1950s America, the rise of suburbs began to take over the country. After WWII, Americans fled the cities for the “American Dream,” as their pockets were now full of cash. A mix of racial fears and affordable housing fueled the need for a suburban “escape.”

White picket fences, cookouts, and look-a-like housing were all the rage for suburban communities, giving families the illusion of peace and safety.

Sure, a suburban neighborhood may seem perfect on the outside… but within these communities reeks the smell of repression, paranoia, and death.

Vivarium

Vivarium is 2019 thriller dissecting the general idea of suburban families and their need for conformity.

The film is presented more as a surreal location. The neighborhood is full of identical houses, and yet… nobody lives there. Our couple—Gemma and Tom—are the only two residents of the entire neighborhood. They never see a neighbor, a delivery person, or even a stray passerby. They are in isolation, imprisoned in an artificial neighborhood.

Vivarium takes the concept of perfectionism to the extreme, showing how a cookie-cutter lifestyle can strip away your autonomy and authenticity as your own person. The longer the couple stays in the neighborhood, the more their mental health spirals.

But it doesn’t just stop at isolation—they’re met with a random baby delivery. Maybe it’s by stork, considering Gemma and Tom are just wanting to escape their new hell by this point. Along with the baby is a note that reads: “Raise the child and be released.”

As they are forced to live with this new child, they soon realize the baby is an uncanny imitation of a human. 98 days in, the baby grows to the size of a 10-year-old boy and is screeching for food. There’s no real conversation with the boy, simply needs and wants.

By the time the boy grows into a young adult, Tom has fallen ill. Although Gemma begs for the boy to bring medicine, he simply tells her it’s time for Tom to be released. Thus, Tom dies.

At the end of the film, Gemma also dies, as the boy explains that all mothers die after raising their children.

All of this, of course, is a weird and crazy metaphor for the harsh realities of suburban family life. Couples move in, feel pressured into having children because everybody else is, and eventually die for the cycle to continue throughout the generations. The suburbs act as a generational prison, as the pressures of being perfect fall onto heavy shoulders.

After all, there’s no escaping the “perfect” life. Don’t you have it all—a home, a car, a job, children?

It’s a sinister look into how family life is condensed and packaged into a factory box, but also how people are silenced into simply conforming. If you’re made to feel like you can’t talk about it… then you don’t. You suffer in silence.

This pressure to conform perfection isn’t new… and it has roots in some dark statistics.

(For those who are sensitive to issues about suicide, skip this section.)

In 1967, a study about suicide in the United States from 1950-1964 was conducted by the NCHS (CDC), in which they concluded that suicide was higher in divorced white men. However, there were other interesting details to note: white women in their 40s and 50s were more likely to commit.

With this historical context, it makes Vivarium feel much darker. Perfectionism during the midcentury was expected, not optional. If you divorced, you were seen as a failure. If you couldn’t keep a job as a man, you weren’t a real man. If you didn’t enjoy the idea of being a mother, you weren’t a real woman.

(SECTION CONCLUDED.)

These expectations, coupled with the stigma of mental health during that time, forced people to suffer behind smiles. Vivarium, then, take this internal suffering and forces it outward. Parents feel trapped by their children, children feel trapped by their parents, families feel trapped by perfectionism.

It is an endless cycle of pain, all for performance.

Fright Night

Fright Night (1985) takes suburban paranoia to an entirely new level.

When Charley is convinced that his next door neighbor is a vampire, nobody believes him. Although his neighbor, Jerry, shows the obvious signs of vampirism, it’s tough to prove that to everybody else.

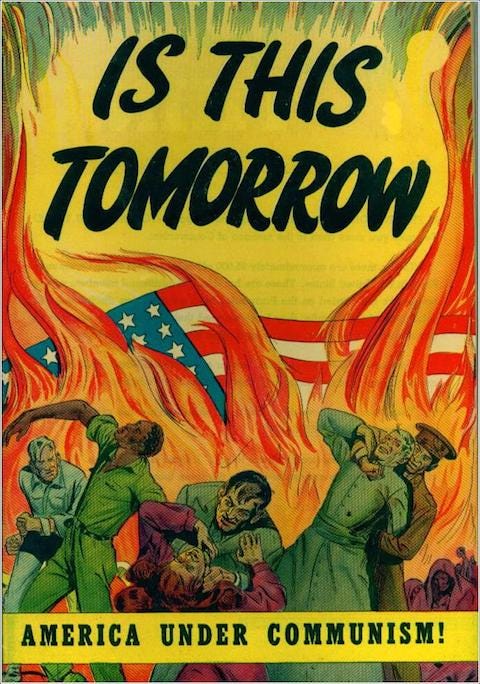

While this film focuses on how a teenager defeats his devilish neighbor in the 80s, it bears a striking resemblance to The Red Scare of the 1950s.

During the 50s, politicians would tell Americans to stay alert—as citizens, you had to look over your shoulder in every corner. Communists could be anywhere, as they were infiltrating our lives. They could be your coworker, your barber, they could be… your neighbor.

This was during a peak time of the Cold War, where tensions between America and he Soviet Union were starting to boil. The Red Scare took over the country, with many people fearful of the secrets their neighbors may hold. The suburbs became a silent war zone.

In Fright Night, Charley is trying to expose a different red scare… mostly involving blood-suckers. He isn’t just fighting a vampire, he’s fighting the fear nobody else will take seriously. Isn’t that the most suburbian thing you ever heard?

Parents

Set in literal 1950s suburbia, Parents (1989) is an obvious satirical criticism of the perfect nuclear family.

Parents tackles the repression present within the “perfect” families of the suburbs, where the children are misunderstood and disconnected from their mom and pop.

The 50s were a time of domestic gaslighting. While parents tried to pretend everything was okay to their children, the American landscape was far from ideal. Mothers and fathers held empty smiles and tucked their children into bed while the threat of nuclear war loomed over them.

Children, of course, were not unaware of the ongoing conflicts. In school, kids participated in nuclear attack drills, where they would hide under a desk to “protect” themselves. The fine-and-dandy act that their parents did had good intentions, but it certainly wasn’t fooling anyone.

In Parents, Michael is suspicious of his parents’ meals. His mother, the perfect housewife, cooks elaborate meals every night. His father, who works at the mortuary, is always happy to eat his dinner. While they seem perfect on the outside, Michael suspects there’s something wrong with the meat his father brings home every night.

Although he refuses to eat the meat, he doesn’t refuse to let go of his intuitive thoughts.

Good thing, because his parents end up being cannibals.

There’s also underlying themes of abuse and generational trauma, which I further explored in a separate issue.

Suburbia isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. Sure, it may promise perfect lawns and friendly neighbors… but the reality is that it’s a silent hell. People smile through rotten smells, covering up the garbage dump hidden as paradise.

Great analysis which is spot on. I would offer other movies with this theme; Halloween, Nightmare on Elm Street and Blue Velvet.