Shock or Art: Why All Gore isn't Created Equal

Peeling back the layers of shock value and storytelling

Horror has long suffered from mistreatment in the mainstream media.

Take The Texas Chainsaw Massacre for example, seen as one of the most iconic films in the genre (and of all time), yet was heavily criticized during its release. Perhaps one of the harshest critiques came from Stephen Koch in Harper’s Magazine:

A vile little piece of sick crap which opened… in a nameless Times Square exploitation house, there to be noticed only as another symptom of the wet rot, another step along the way… It is a particularly foul item in the currently developing hard-core pornography of murder… designed to milk a few more bucks out of the throng of shuffling wretches who still gather, every other seat, in those dank caverns for the scab-picking of the human spirit which have become so visible in the worst sections of the central cities.

Koch’s sentiment held true for many in the mainstream at the time, as the horror genre wasn’t seen as a real art form, but rather as an exploitative tool for sickos to get their kicks. For years, horror films were scoffed at or skipped over for daring to stand out against what was popular.

Horror didn’t clean itself up to be presentable in front of an audience but rather revealed the true colors of the very thing it wasn’t afraid to critique. On the surface, critics despised horror for being “adolescent” and “meaningless,” yet much of this unbridled hatred could be the result of seeing their true reflections being exposed.

Horror is no stranger to silly dogpiling, unneeded controversy, and tired Oscar snubs. In fact, horror is quite infamously known for being treated as the redheaded stepchild in film—despite the pleas from fans.

In a way, horror has always been the “outsider” genre that stood out against the others, unafraid to call out the BS that took place in the world.

However, that doesn’t mean there isn’t valid criticism on certain parts of the genre. The rise of shock value horror in particular has become increasingly relevant in an age that’s seemingly desensitized by the unfortunately tragic events in recent years. Shock value in gore especially has become more and more in our face, with each movie trying to one up each other in gross factor.

On the flip side, we also have seen the opposite be true: horror films increasing their storytelling to prove the critics wrong, all while using the “vile” techniques that are often slammed by the media.

While shock can be a valuable tool when trying to express an important message, when does that line blur? When does the shock drown out any meaningful ideas under the gallons of blood? When does the meaningful horror stray too far from the blood?

And… is horror really “adolescent” just because some of the genre refuses to grow?

Gore for the Sake of Gore

Modern horror still suffers from its critics. As shock value horror becomes increasingly more popular, the reputation of the genre becomes based on the gore-heavy controversial films that the media loves to punish.

In their defense, many of these films do lack actual substance, instead focusing on the intensity of the blood splatter.

Terrifier

It would be silly of me not to mention the most viral horror sensation right now: Art the Clown.

The Terrifier series is, in my opinion, the definition of “just because” torture porn. The first film especially lacks in any actual plot. While, yes, there’s a beginning, middle, and end… there’s not any meaning for any of it.

It’s a story being told for the sake of gore, rather than a story using gore for substance. Terrifier doesn’t focus on a plotline because it doesn’t care about a plotline.

The main goal of the series is to shock you with its intense body mutilation. A movie doesn’t just saw women in half and cut their breasts off for a meaningful message… it does it to leave you disgusted. Or elated. Depends on your fancy, I guess.

Terrifier’s villain isn’t even a character. Art is a personification of impulsive evil. He is the persona for unnecessary force. The persona for a love of violence.

Art is what outsiders think horror is. He is the symbol of an immature and grotesque genre to those who never cared to understand what horror means to begin with.

It isn’t until Terrifier 2 that an actual storyline is introduced, but even that is extremely questionable. The plot feels slapped together, like it only exists because audiences begged for more Art, not because there was more story to tell.

While Terrifier 2 revealed that Art is… some kind of… demon (?), the plot is incredibly lackluster. It feels confusing, out there, and yet somehow also extremely generic at the same time. Still, it offered insane kills that people praised, thus resulting in yet another installment with Terrifier 3.

Terrifier 3 attempted to finally create character development with characters like Sienna, who is meant to act as the final girl of the series. While Sienna received character development, Art received an even more convoluted plotline decorated in tacky Christmas lights.

Not only does the film feature a weird birthing scene of Art’s head, but it also touches on the idea of there being portals to Hell. But don’t get it twisted: I understand these films aren’t meant to be taken seriously.

These are films drowned in the idea of being quirky and kooky, as the plot devices rely on humor rather than logic. And here’s the thing… I know that. You know that. But does the typical movie goer know that?

Does this idea of silly torture porn go down the gullet in others as easily as it does for the casual horror fan?

After all, this series focuses all its value on its shocking kills because that’s all it cares to offer. There’s no substance in the Terrifier series because there doesn’t really need to be.

The issue comes when Terrifier becomes the face of horror in the public eye, causing the genre as a whole to still struggle from unfair criticism. See, the issue isn’t that Art the Clown exists… the issue is that he has become the mascot of modern horror. The biggest horror franchise right now is about cruel dismemberment for the sake of cruel dismemberment.

With no narrative weight, the public’s view of horror gets skewed into thinking that the Terrifier films are what all horror is. These types of series worsen the stereotypes seen by outsiders on the genre, confirming their suspicions.

Should we not listen to their critiques simply because they “just don’t get”? No, I think there’s actually validity in both sides of the spectrum—because, sometimes, horror is just senseless. And that’s okay.

The Human Centipede

While Terrifier has a huge fan base, The Human Centipede is… less than loved by the general public.

It’s widely accepted that The Human Centipede is a bad movie. It’s also widely accepted that it was an unnecessary movie—and while, yes, you can argue any movie is unnecessary… The Human Centipede feels more like a fever dream than an actual coherent thought.

In watching The Human Centipede, you realize that the story for the film was simply created as a vehicle to showcase the disgusting and vile human experimentation of whatever the hell a human centipede is. The story is pretty generic, relying on the mad scientist trope and not really diving much into the why of anything.

Hell, the movie even spawned two sequels—each one more desperate to outdo the last

However, if you asked Tom Six, the director of The Human Centipede, he would say that it’s a film that reflects the horrors of fascism. Six claims that he was inspired by the horrific Nazi experiments that took place during WWII, thus resulting in the villain surgeon of the film being German. That’s also why, apparently, the victims of the film are American and Japanese.

Do I think that’s true? Sure, I could totally see how the human experiments performed by Nazis could inspire something like The Human Centipede. But calling it a warning about the dangers of fascism feels like a stretch.

This film was created as a gross out film. That’s it. That’s the entire point of the movie and nobody can convince me otherwise. A film about sewing mouths to anuses has no other meaning to it other than to absolutely disgust you and possibly make you vomit.

The depravity of a doctor’s fantasy of wanting 500 people to be sewn together to share a singular digestive track holds no place in “meaningful” art. I’m not usually one to say that, especially because it sounds so snobby… but I don’t know, it feels like I need to say that for some reason.

When the film first released, it was met with mixed reviews… but mostly negative. I have to say, my favorite review is from Roger Ebert:

"I am required to award stars to movies I review. This time, I refuse to do it. The star rating system is unsuited to this film. Is the movie good? Is it bad? Does it matter? It is what it is and occupies a world where the stars don't shine."

Do I think this movie is the worst movie ever made? No. Of course not. Do I think this movie affects the reputation of the horror genre? To some degree.

This movie is not only vile… but it’s seen as a joke. And at this point, I’m too scared to ask if this movie was originally meant to be satire or if it just became satire because of the public perception of it.

Regardless, its controversy caused quite a stir. This is a movie of nasty, almost fetish-y gore just so it could say it has it. This was a film made to cause a reaction, rather than a film trying to actually say something.

And it wasn’t just controversial; it became the center of shock-value internet lore and viral memes.

Thus, public perception is skewed in looking at the horror genre: this genre is just… made to gross you out. To make you feel nauseated. It doesn’t actually have anything to say.

None of that is true, of course. But it’s easy to see how some people come to that conclusion when films like The Human Centipede exist.

Again, the problem isn’t that The Human Centipede is a thing… the problem is that The Human Centipede tries to be something it’s not. And when this movie is the punchline to every “what’s wrong with horror” joke… it’s hard for the genre to be taken seriously by people who already think it’s trash.

Megan is Missing

Out of all of these, Megan is Missing is a strange case. The film was created as a PSA about the dangers of child abduction, yet it comes across as an unnecessary exploitation film instead.

The movie follows two teenage girls, Megan and Amy, focusing in on overly-sexualizing the titular character.

Megan is Missing came out in 2011, but it found popularity in 2020 where it became a viral challenge on TikTok. It became a trend for people to say the movie “traumatized” them due to its disturbing imagery. It became so prevalent that Michael Goi—the film’s director—even issued a trigger warning:

“Do not watch the movie in the middle of the night. Do not watch the movie alone. And if you see the words 'photo number one' pop up on your screen, you have about four seconds to shut off the movie if you're already kind of freaking out before you start seeing things that maybe you don't want to see.”

Now, was this trigger warning to capitalize on the TikTok virality? That I’m not sure of, but I am sure of the intensity the last 22 minutes this film has to offer.

At its core, this movie is meant to shock viewers. There are no ifs, ands, or buts about it—this is a horror movie based in shock value because it felt the only way to tell its message was through shock value. The issue is that this film focuses entirely too much on the wrong things.

The oversexualization of minors, the trauma porn, the need to dive way too deeply into a three-minute rape scene. This is a movie that could’ve touched on the horrors of kidnapping without showing any of this yet chose too regardless.

Some may defend the movie by saying “this happens in real life,” but film is an art medium of choices—and choosing to show drawn-out child assault scenes for the sake of “realism” crosses a line between awareness and exploitation.

Megan is Missing isn’t even a good movie. It’s low budget with poor acting, accompanied by a lackluster plot that exists solely to place two girls in a scenario of extreme victimization.

The ending of this movie does go overboard. And I’m not going to really speak much about it other than the fact that it feels completely indulgent rather than cautionary.

However, I can see the argument of that this movie did make an impact on people and possibly made a few individuals second guess who they spoke to online.

But when this is the type of stuff going viral on TikTok, it concerns me about the state of the horror genre. This isn’t a film that deserves to be shared, but because it did, the reputation of a genre so rich in story and real meaningful cautionary tales is seen as an exploitative force.

Horror deserves better representation than a trauma bait film. It’s a genre of nuance, intention, and meaning… especially when speaking about real-world issues.

When Pain Has Purpose

While there may be plenty of horror films that focus on painting the walls red, there’s also plenty that care about telling a story that means something. All the while, these films also partake in insane gore but elevate it with a little narrative weight.

The Thing

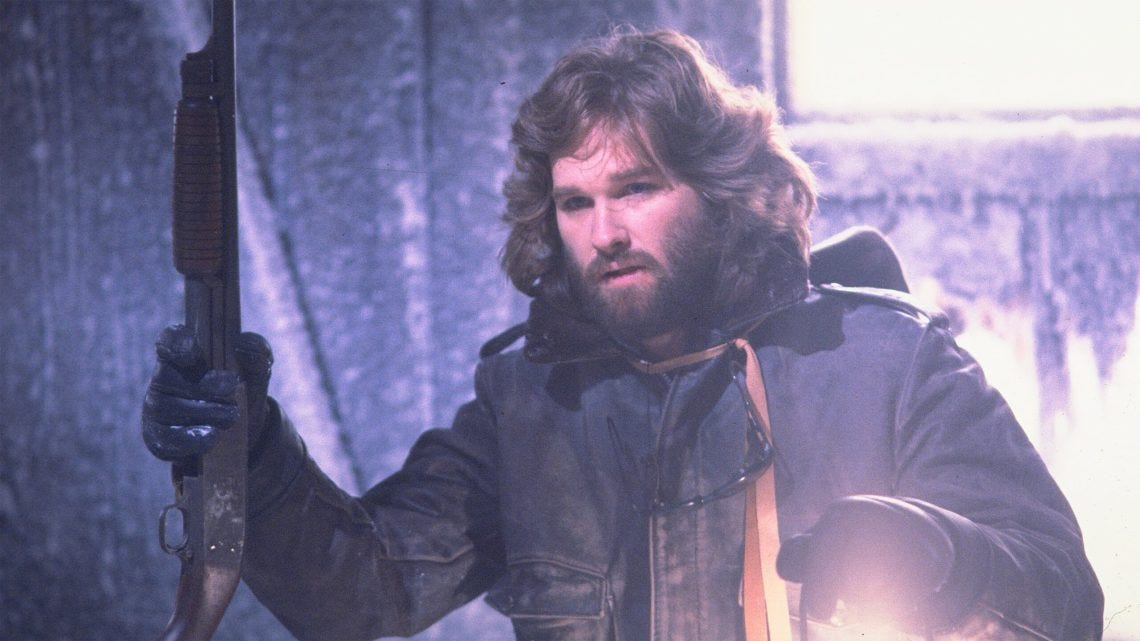

For years, The Thing has been praised for its practical effects. Even today, it stands out in a sea of modern technology for its groundbreaking creature design that stays in our nightmares.

The Thing needs no introduction. It’s a cult classic for a reason, known for its suspenseful atmosphere and eerie “whodunnit?” undertone.

This is a film rich in body horror. Everywhere you look is another disgusting creation with blood and guts spewing out somewhere. But under all the gore is a message about the effects of isolation and a criticism on government authority.

Released in 1982, The Thing was tasked with calling out the effects of isolation and paranoia caused by the Cold War. The film, which takes place in an Antarctic U.S. research base, understands that the average American had been led to believe that even their coworkers could be communist spies.

The Thing played into this fear, morphing its cast into vile and hostile creatures. See, The Thing was certainly gnarly, but it had something to offer in all its nastiness.

But even in 1982, The Thing faced its own issues. The film was slammed negatively, being cited as “boring” and “nihilistic.” Its anti-authoritative stance was not something people were very happy about.

Ironically, critics felt that The Thing lacked in any meaning. Linda Gross of the LA Times said that the film lacked in feeling. And, surprise, David Ansen of Newsweek said that it lacked drama because it was “sacrificing everything at the altar of gore.”

You and I both know that these reviews are full of it—there is very clearly meaning within the story of The Thing. It wouldn’t be a John Carpenter project without some kind of message underneath the horror. We know this film as a master in practical effects and a warning in governmental influence. And yet, this is the same movie that people called repulsive and narratively thin at the time of its release.

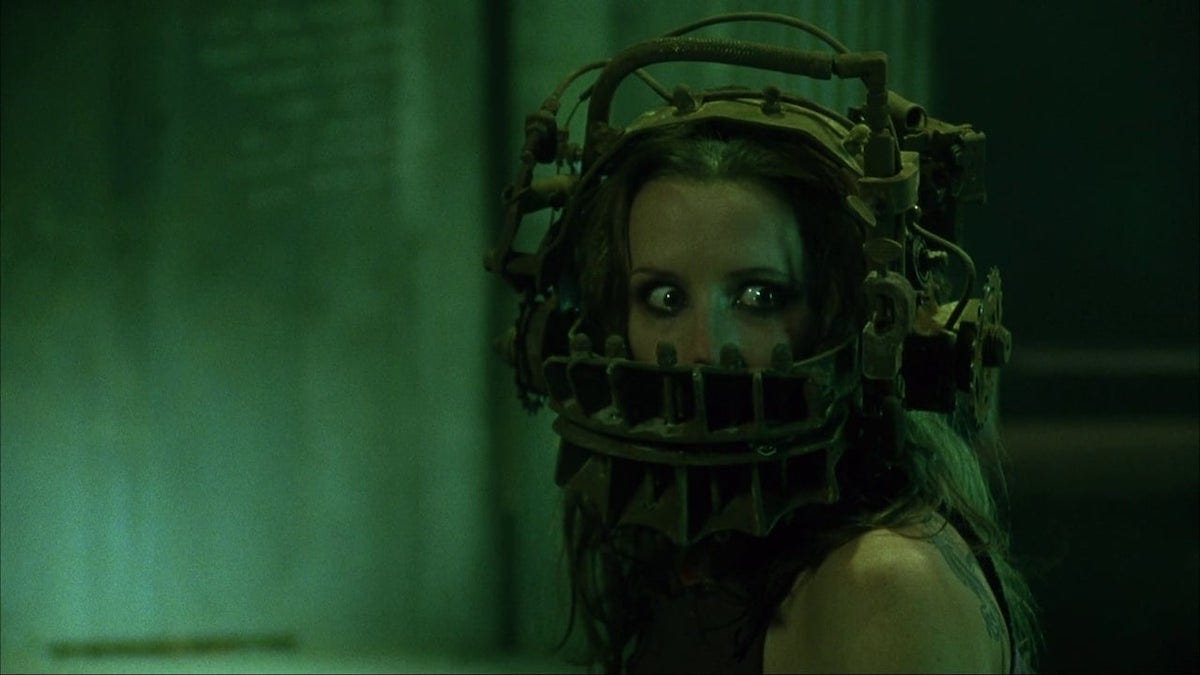

Saw

The Saw franchise is no stranger to controversy. Despite being filled with crazy kills and pretty intense gore, Saw has always been about its message first and foremost.

The Saw franchise would be seen as another cash grab splatterfest if it weren’t for John Kramer, whose character plays a central role as the master puppeteer in the series. Kramer is the judge, the teacher, and the philosopher.

His role in Saw serves as a warning to those who deserve punishment for their sins. In some regards, he is the dark angel archetype, twisting his morals to teach a lesson that would otherwise be lost.

See, it’s silly to say that Saw is just another torture porn fest, because Kramer isn’t killing people out of some sick and twisted fantasy. No, Kramer is playing “games” with people, allowing them the chance to escape if they sacrifice something in return.

Saw’s entire plot is centered around the idea of understanding that you must pay for your sins… but also of understanding true gratitude. As said by Kramer himself:

“Most people are so ungrateful to be alive. But not you. Not anymore.”

And yet, despite the message being obvious (like, seriously, this is practically a bullet through our heads), some critics still chose to ignore it. Instead of taking in what the first film was trying to say, critics just labelled it as another run-of-the-mill horror movie. Saw was “too convoluted” and apparently a Seven rip-off.

But would anyone have even listened if Saw never cut through a bone?

The Substance

The Substance was one of the biggest films of 2024.

The film was a critique on how beauty standards cause vulnerable women to seek miracle cures to “fix” themselves. At its core, The Substance is meant to call out the beauty industry for its predatory treatment toward women.

In doing so, it utilizes body horror as a visual metaphor, showcasing what the beauty industry does to the average woman. The gore in this movie acts as a stand in for the visceral pain that women face in their insecurities. Despite how much they try to keep up appearances, nothing is ever enough.

Compared to the other films mentioned, however, The Substance was the only one to get generally positive reviews all-around. Perhaps it’s because The Substance is so in your face about it, or because it would be stupid to make a mockery out of a film literally tearing down beauty standards by calling it “splatter trash.”

I don’t really know.

It was actually one of the only horror films (along with Nosferatu) to be featured at the 97th Academy Awards, even scoring an Oscar for Best Makeup and Hairstyling.

The Substance proved what we’ve always known: gore isn’t the problem. It’s not about horror evolving, it’s about the audiences finally catching up.

Why Does It All Matter?

There’s an interesting dilemma in all this for the horror genre: damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

Even films that give meaning to all of their gore are quick to be beaten down, cornered into being described as just another bloodbath for a cheap thrill. For something like The Human Centipede to have gotten similar remarks to that of The Thing upon release, you begin to realize that some people just don’t like horror movies.

Not everybody is a fan of blood and guts, which is certainly fine, but it becomes a problem when your dislike of gore affects your overall judgement on a film’s quality. When these movies are all downvoted by outsider critics, horror’s reputation as a whole is tarnished. Suddenly, it’s back to the 1980s when you catch a horror flick in hopes to see some tits instead of watching for any real storyline.

It doesn’t matter if a horror movie is a masterpiece. If the film tells a beautiful story but dares to incorporate gore, it might as well be seen as bloody pretentious trash.

The fact of the matter is… some people will never see horror as a valid art form. And that’s the thing: all art is art.

Even the art that doesn’t seemingly have any meaning is still art. Art for the sake of entertainment is just as valid as the art with meaningful message. The abstract paintings still line the walls of the museum even if you don’t think they count, because at the end of the day, they’re still art even if you like it or not.

There’s a place for films like Terrifier in the horror genre because there’s a place for movies like The Substance. Disregarding one over the other is unfair to a genre that’s so rich in all kinds of scares.

So, why does it even matter?

Because I’m not writing this as a plea to the critics who don’t wish to understand the genre. I’m writing this as a reminder that it’s okay to do whatever the hell you want.

There’s always going to be critics in your way. There’s always going to be naysayers. There’s always going to be bad actors in disguise.

But that shouldn’t stop you from shining your light.

You may always be an outsider in comparison to the rest of the world, but you burn brightly as a star in the communities that accept you.

And that’s exactly what horror is: a genre that will never quite be understood by the broad public no matter how much it tries to prove itself… but when it does, it torches the competition with its unique angle and approach.

Because, at the end of the day, horror has always had a place for both the mess and the meaning.

So… maybe we should all be more like horror. Minus the killing and guts.

excellent post. I like the comparrison you used contarsting how some movies use gore for the sake of shock while others use it to enahnce the plot

A very thorough analysis here. I enjoyed reading it. One of my favourite horror films is Takashi Miike’s Audition (1999), which has received criticism for the climactic torture scene. If you’ve seen the film, what are your thoughts?