Oh, to be a father.

To hold your child close. To be the protector of such a small human. To push them on the swing one day and to read them bedtime stories the next.

Fatherhood is full of joys. Just as I mentioned with the Mother’s Day issue though, it’s also full of complexities.

Being a parent doesn’t just mean providing your child with love and protection, it also means reflecting on your own shadow. To parent, you have to understand your own flaws… your mistakes… your grievances. You have to break cycles.

In horror, these cycles are rarely brought to a close. Instead, they continue to grow bigger and bigger, with fatherhood becoming a villain of intense emotional insecurity.

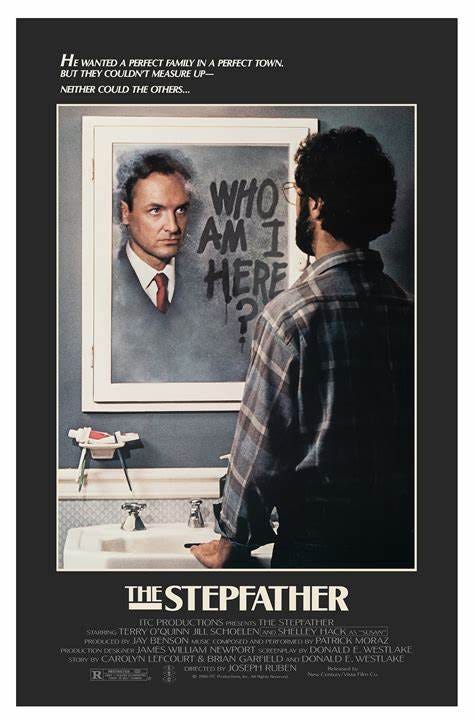

The Stepfather (1987)

The Stepfather follows Jerry Blake—aka Henry Morrison—as he goes from family to family marrying single mothers. Jerry isn’t just a widow-chaser though… he’s a serial killer.

Once he’s finished with a family, he hacks them up and changes his identity. His entire character is the personification of control and order. He wants perfectionism within each of his families, and once that illusion escapes him, he erases their existence and the identity he made with them.

He’s meant to be the exaggerated father of control, acting as the stand-in for his real-life counterparts. The father that tracks his children’s whereabouts, snoops into their rooms for any drugs, and is overly protective to the point of smothering. IF anything is out of order, there’s a stern talking to.

But for Jerry, this concept goes further. The overly protective father figure is turned homicidal, stalking his prey to see when they fall out of line just enough for him to justify his bloodthirst.

Jerry’s life is based in the concept of a white picket fence with his loving family acting as the perfect 1950s sitcom archetype. The issue is that he’s dealing with real human beings, and nobody will ever quite measure up to Jerry’s wants.

Yet, when his stepdaughter finally stabs him in the chest to end his killing spree… he tells her “I love you” before tumbling down the stairs.

Even in his fleeting moments, Jerry’s need for control sticks with him. There’s no genuine love and care in his final breath, but rather another way to manipulate his new family. That “I love you” is meant to haunt his stepdaughter with guilt, not a tender declaration to remember him by. For Jerry, family wasn’t about love. It was about control.

The Shining (1980)

The Stepfather explores the dangers of overprotective fatherhood. The Shining, on the other hand, focuses on the terrifying cycles that can come from broken family dynamics.

In Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 film adaption of the famous Stephen King novel, Jack Torrance is presented to us as someone already deeply troubled. He’s erratic and seemingly unhinged, unconcerned about the uprooting he’s putting his family through by taking up the job of watching over the Overlook Hotel for the winter. For Jack, there’s only one concern: writing his novel.

However, the hotel is in total isolation. With snow storms blasting in through mountain roads, there’s no way to escape other than using a specialized snow vehicle.

Throughout the film, there’s remnants of Jack trying to be a father, but every attempt is shrouded in the unfortunate context of his past actions. We, the audience, know that Jack has hurt Danny before during a drunken rage. We know Jack struggles with drinking, and isolation is the worst place for someone in a battle with addiction.

As the months go by, Jack becomes more and more affected by the lack of human connection. He becomes far too invested not only in writing his novel, but also by protecting the hotel. Jack’s inner demons begin feeding his delusions of authority, and his role as a father becomes twisted. Jack is stripped of his protective power, and to Danny, becomes nothing but a monster.

The entire sequence of The Shining reflects the real-world horrors many children face. Their fathers turn to substance abuse, rather that be through drugs or alcohol, and they slowly watch their protector turn sinister. In some cases, it becomes a cycle within, but in others… the child is able to break the chain.

What The Shining shows us isn’t a father becoming a monster because of a haunted hotel—it’s a haunted hotel giving a monster the spotlight.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)

Everything’s bigger in Texas, including the generational trauma. The Sawyer family of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is by far the best example of this.

“Cook,” aka the father figure of the family, acts as the leader. He’s the one teaching his brothers the sick pleasures of human consumption. He’s also the one teaching them the disgusting pleasures of violence and abuse.

Cook is essentially the shadow of fatherhood, pushing all of his own ideas and traditions onto his younger brothers. However, these inhumane traditions carry on into their own family relations, as Leatherface is made out to be a victim of the abuse. Obviously, Leatherface isn’t exactly innocent, but being an evil-doer doesn’t mean you can’t have evil done to you as well.

According to Tobe Hooper, Leatherface kills out of fear. He’s been conditioned into believing that the only way of survival is violence, as taught by his unhinged eldest brother. It is especially concerning considering Cook never does any of the killing, but rather makes Leatherface and Hitchhiker perform the acts. In doing so, he takes a step back and watches their behavior in the shadows, simply cooking up meals after the deeds are done.

Cook is a silent villain. He’s not necessarily as terrifying as his brothers, but he’s definitely more twisted. It’s not just about what he teaches them, but rather what he enables. He is the patriarch through control, fear, and nasty tradition. His version of “fatherhood” isn’t about being a loving role model, it’s about growing the bloodthirst of killers while never having to lay a hand on a wriggling victim.

Pet Sematary (1989)

Out of the films discussed, Pet Sematary is about one of the healthier father figures. Louis is a loving father, but when his son, Gage, tragically dies, he becomes deranged with grief and guilt.

Pet Sematary decides to use a different aspect of fatherhood for its horror instead of abuse, addiction, or control. Instead, it focuses on the feeling of being a failed father.

Louis is desperate to bring his son back to life. In his stage of grief, he seemingly stays stuck in denial. This, of course, is because he feels like he failed into protecting his own child. In his mind, it’s his responsibility to keep his children safe… so when something like a tragic accident strikes, he feels as if he failed in his duties.

Louis isn’t the monster in Pet Sematary. His grief and desperate need to undo what he believes is his fault are what haunts him. Instead of seeking grief counseling, he seeks out the unthinkable.

He turns to the instability of resurrection, hoping to bring his son back. He doesn’t want to play God, but rather he wants to erase his failure as a father. If he can bring back Gage, then all of his guilt, pain, and sorrow will go away. But that’s the thing about fatherhood: it isn’t about clinging to control. It’s about love. And as the old saying goes: “If you love something, you have to let it go.”

Louis isn’t evil, he’s just heartbroken. That’s what makes Pet Sematary such a gut-wrenching story.

Conclusion

Fatherhood in horror isn’t always about love (in fact, it rarely is). It’s about control, repression, and denial. Films exploring fatherhood often shows us one universal message: it’s okay to not be perfect.

No parent—mother or father—will ever be perfect. There will always be a fear of messing up. A fear of failing your children. A fear of becoming the monster you try to protect your children from. A fear of not being the best parent they deserve.

But that’s okay. It’s normal to have those thoughts.

The fathers in horror films are haunted by their own issues. They reflect our inner demons. Our inner monsters. But they are the exaggerated beings of warning.

A father is there to love their child and provide them with the best life they can have… even if it’s imperfect.

To all the fathers out there: Happy Father’s Day.